From Brasilia, a Call for Governments to Work for Indigenous Peoples of the World Towards COP30

/in News/by GATCIndigenous Peoples of Brazil met with over a dozen of Brasilia’s ambassadors to call on governments to support their agenda towards COP30 with swift action to stop deforestation and violence in indigenous lands.

April, 2024 — Brazil’s indigenous movement is seeking multiple pathways to ensure the upcoming COP30 can be marked by action in the territories. In a meeting with over a dozen embassies, they asked governments to commit to halting their countries’ extractive activities in indigenous lands. As the country gears up to host the upcoming COP30, there is a need to match discourse with on the ground action, according to the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB).

During the meeting, leaders from all biomes of Brazil stated the links between land invasion and foreign interest, particularly highlighting the violence communities experience due to displacement and confrontations with invaders and corporations.

“Don’t receive soy exports that are linked to indigenous blood. If a product is coming from our lands, it is the result of a direct attack on us and is tainted by violence”, said Norivaldo Mendes, from the Guarani Kaiowa people and Executive Coordinator to Aty Guasu and APIB. “Corporations won’t tell you where the soy comes from because they don’t want to lose all the resources our land provides them”, he finished.

The delegation met with representatives from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, the United States, France, Italy, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the Brazilian Ministries of Foreign Affairs and of Indigenous Peoples. This marks the first time the APIB hosts a single meeting with a diplomatic body of this calibre.

Among the petitions from the indigenous leadership, they called on these governments to support effective Indigenous participation in COP30 and to include concrete goals for demarcating Indigenous Lands in the upcoming update of the Brazilian Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs); to implement direct financing to Indigenous organisations by adapting their operations, monitoring and evaluation instruments; and to prioritise a new vision on infrastructure that respects Free, Prior, Informed Consent and that does not impact Indigenous Lands – explicit demanding no mineral or oil exploitation in their territories.

The ambassadors heard a call for them to hold companies accountable for damage incurred against nature and the inhabitants of the regions in which they operate; and to commit to not financing or supporting projects that are characterised as greenwashing.

“We want to push for traceability of the commodities sold to the European Union and big economies of the Global North, because then you will be able to see why we are constantly calling out violent land grabbing attacks” said Dinamam Tuxa, Executive Coordinator to APIB.

The leadership also pushed a debate on mining expansion as a response to the climate crisis and a proposal for “sustainable” development. “There is no point in coming to Brazil to look for what has already been used up in your countries”, said Executive Coordinator Kreta Kaingang, speaking on fossil fuel and mining projects. “We are not against development, but we cannot accept development that is based on the death of our people”, he added.

The Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC) leadership joined Brazilian Indigenous authorities for the meeting, as part of their participation in the Free Land Camp (Acampamento Terra Livre – ATL) to advance a joint agenda towards COP30 and call on other stakeholders to join their efforts. Their presence showcased the articulation between Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities worldwide.

“On behalf of the Indigenous Peoples of our alliance, we want governments to join us to make COP30 a historic turning point in how the world confronts the climate crisis. If we don’t come together, we might have to sit down to write the history book on how humanity failed to live with Mother Earth”, said Rukka Sombolinggi, in representation of the Indigenous Peoples of Indonesia and the GATC.

Representatives from the embassies acknowledged the guardianship role Indigenous Peoples carry in their territories and pledged to continue on dialogues with APIB in the route to COP30. Moreover, they spoke of their standing projects and the will to continue investing and connecting with the communities. Many promised to work both with indigenous organisations and the Brazilian government to accelerate the demarcation and effective protection of indigenous lands, guaranteeing the autonomy of the people, and strengthening territorial governance.

Brazil Creates an Indigenous Task Force to Advance Land Rights in the Country

/in News/by GATCIndigenous land titling in Brazil has fallen behind as president Lula had promised to complete 14 processes in his first 100 days of government, but had only titled 10 in over a year in power.

April, 2024 — President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva met with a delegation of 40 indigenous leaders from across Brazil last Thursday (25) afternoon at the Palácio do Planalto. The gathering, which took place during the 20th edition of the Free Land Camp (Acampamento Terra Livre ATL)- the largest indigenous mobilisation in the country- concluded with the creation of a Task Force to advance land titling.

The meeting followed a massive march where eight thousands of Indigenous Peoples and Civil Society Movements filled the city’s central area with echoing chants and energetic calls for the government to advance land titling and stop large projects that pose threats to their territories. The rally ended at the Praça dos Três Poderes, where groups of indigenous organisations continued on with their protest as the meeting took place.

Photos: Kamikia Kisedje

The Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) had been denouncing the government’s failed promise to title 14 indigenous lands in the first 100 days of Lula’s government. In over a year they had titled 10 of those lands, whilst many others awaited. Moreover, they raised alarms as Congress debated passing a law that could severely limit their rights to land, the Time Frame Law (Marco Temporal).

“In our understanding, there is no legal impediment to land titling. What there is is a political impediment, which we hope will be resolved with this task force, which is a demand from the indigenous movement, so that we can actually unblock land demarcations. Not only of the four lands, not only of the 25 lands with declaratory ordinances [already signed], but so that, once and for all, we can overcome administrative and political issues for demarcating indigenous lands in the country,” said Dinamam Tuxá, a Executive Coordinator to APIB.

Responding to the primary demands of APIB, the government announced the establishment of a governmental task force aimed at unlocking pending land titling processes awaiting presidential approval. Priority will be given to four key areas–including the Xukuru e Morro dos Cavalos- each mired in disputes awaiting resolution.

The task force, chaired by Minister Guajajara, will collaborate with key governmental bodies, including the Office of the Presidency, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Farming, the Attorney General’s Office (AGU), and the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai).

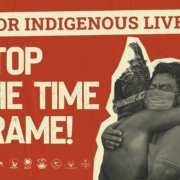

Indigenous movement mobilised against a bill that severely hinders their rights and projects harding their territories

During the 20th edition of the Free Land Camp (Acampamento Terra Livre), Indigenous Peoples took over Brasilia’s streets with over 8,000 thousand peoples from over 200 distinct indigenous ethnic groups. In their chants, they argued against the Time Frame Thesis (Marco Temporal) and large projects like the Ferrogrão which threaten their rights and territories.

The “Time Frame thesis” is a legal concept asserting that Indigenous peoples are entitled to claim only the lands they inhabited exactly on October 5, 1988, the date of Brazil’s Constitution promulgation. The proposition does not acknowledge the centuries old history of Indigenous Peoples of the country and does not account for the forced displacement they suffered during Brazil’s dictatorship in the 20th century. As a response, the indigenous movement united under the “Our time frame is ancestral” argument.

Indigenous leaders walked through Brasilia next to a large truck that was wrapped to simulate a “train of death”, signaling their opposition to the Ferrogão railing project. The new train route would cut through sacred indigenous lands in the Amazon to facilitate soy exports. Monoculture of soy is one of the leading causes of deforestation and land grabbing, and the train would only aggravate the circumstances.

Donors Struggling to Deliver Climate Funds to Indigenous Peoples

/in News/by GATCAlliance of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities from the forests of Africa, Latin America and Asia releases a report at COP28 suggesting donors are struggling to deliver promised climate funds directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

As UN negotiators debate how to invest trillions, experiences and evidence presented at Dubai event suggest funds channeled through third parties ‘evaporate’ before reaching communities shown to excel in restoring forests and preventing deforestation.

DUBAI — (3 December 2023) At the UN Climate Conference today, a global alliance of Indigenous Peoples and local communities from 24 tropical forest countries released a report identifying significant flaws in global efforts to fund communities that conserve some of the world’s most biodiverse and carbon-rich tropical forests in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

According to research released today by the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC), donors continue to use inadequate, antiquated systems for documenting and delivering development assistance, often sending money for Indigenous Peoples and local communities through third parties, limiting the amounts that reach them. For their conclusions, the authors drew on information provided by Indigenous Peoples and local communities; a review of publicly available donor data; a survey of partners and allies; and insights gathered during a workshop in Paris to discuss obstacles and solutions for tracking funds and reporting impact.

“We are committed to working with donors to build a system that can work for both of us,” said Mina Setra, an Indigenous Dayak Pompakng woman from West Kalimantan, Indonesia and the Deputy to Secretary General of AMAN (Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago), an Indigenous organization with 2,565 member communities. “We believe that by doing so, we can scale up our contributions.”

Indigenous Peoples in Asia at the Nusantara Fund launch. Photos: TINTA

Presented today at a side event during COP28, the GATC findings are being released as UN climate negotiators prepare to hammer out an agreement worth trillions of dollars for implementing and financing “nature-based” and other solutions to address the climate crisis. An estimated 36% of the world’s remaining intact forests, at least 24% of the above-ground carbon in tropical forests and up to 80% of the world’s remaining forest biodiversity are found within Indigenous Peoples’ territories. And yet the UNFCCC’s first global stocktake stopped short of calling for funds to support the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and their proven, outsize role in conserving and restoring tropical forests.

In detailing their findings, the authors of the GATC report concluded that only a small fraction of international funding for biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development is allocated for Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Where data is available, they highlight the pervasive discrimination faced by Indigenous Peoples and local communities but also their crucial role in combating climate change and biodiversity loss and achieving sustainable development that leaves no one behind.

GATC leaders say that the intersecting crises of climate change, biodiversity loss and inequality are making it difficult for them to maintain a sustainable way of life, and to pass down their traditional knowledge, practices, and innovations to future generations. Data from the ground illustrates how little money is reaching communities. A survey among members of the GATC suggests that few local organizations in their networks operate with budgets above US$200,000, and many local organizations have an annual budget below US$10,000. Communities are asked to do big things with small money, according to the GATC report.

The double challenge of too little information about too little funding is echoed in a second report, which was released on Friday by the Forest Tenure Funders Group (FTFG), which is comprised of donor countries and philanthropic organizations that made a collective commitment at COP26 in Glasgow to deliver a total $1.7 billion in five years directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The Forest Tenure Funders Group reported that figures cited in last year’s report overestimated the amount of money delivered directly to communities; it was actually 2.9%. While the amount of funding for communities increased modestly to $8.1 million in 2022, the overall percentage of direct funds declined to 2.1%, despite the group’s commitment to increase direct support.

“The philanthropic organizations and donor governments that made the US$1.7 billion pledge in Glasgow, really want us to succeed, but the percentage communities receive under the pledge has dropped from 2.9% in the first year to 2.1% in the second year,” said Levi Sucre Romero, a Bribri leader from Costa Rica who serves on the GATC council and chairs the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests (AMPB). “This means we are going backwards; it is becoming more evident that it is hard for donors to trust us with the money that we need to scale up our guardianship role.”

Ford Foundation President Darren Walker, who wrote an introduction to the Forest Tenure Funders Group report, acknowledged the problem, noting that donor practices and priorities “are not changing fast enough.”

“Stated simply, funding remains insufficient, inequitable, and inflexible,” the Ford Foundation president wrote in his introduction. “In 2022, an unacceptably small volume of funding—only $8.1 million—flowed directly from pledge donors to Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants. I am disappointed by our slow progress on this point, and I know our Indigenous, local community, and Afro-descendant partners will be, too.”

Indigenous-Led Solutions to Correct Flawed Systems for Delivering Aid

In November, the GATC hosted a two-day workshop, drawing to Paris 65 representatives of Indigenous Peoples’ networks, local communities, national donors, philanthropic funders, UN and multilateral agencies, civil society organizations and researchers. Held under Chatham House rules, the event contributed to the report released today by the GATC.

Workshop participants agreed on the need to correct the systemic gap identified in the report and to work together to build a better tracking system, drawing on data from multiple sources, including Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Currently, reporting is based on estimates, ad hoc methodologies and surveys, which are complex and time consuming, and carry significant risks of miscalculations, misinterpretations and double counting, according to the report released today. The goal will be to develop a plan for addressing the lack of answers to basic questions including, how much money is earmarked for Indigenous Peoples and local communities, for what purpose and with what impact.

Shandia leads policy and high-level dialogue to facilitate funding to Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

In reporting on the challenges they face attracting direct funding for their communities, the GATC members said they are grateful for the partner NGOs whose mission aligns closely with theirs and who receive funds that are earmarked for supporting Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

“This is not an argument for taking funds away from our closest partners and allies,” the GATC report notes, “but points to the immediate need to scale-up funding to our organizations to create a level playing field.”

Efforts to collect data for the GATC report revealed that Indigenous Peoples and local communities often remain excluded from discussions about funding for their own territories and organizations. Global systems for reporting development aid through the organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) also failed to track funding for Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

“We urgently need to turn things around, yet progress is painfully slow,” said Lord Goldsmith, who was Minister of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office of the UK Government when he joined other high-profile donors in making the pledge in Glasgow. “The money often appears to evaporate in complex transactions through numerous layers of multilateral institutions, raising concerns that too little is being done to support the quest of Indigenous Peoples and local communities for their land rights as a climate solution.”

In response to the situation, leaders of organizations representing thousands of Indigenous Peoples and local communities across the globe have established funds and other mechanisms that can directly channel funding to communities.

According to the GATC report, these funds support community activities, while also helping to build technical capacity and develop indicators and priorities that suit the communities and help them measure and report on impact. “Their design is based on extensive consultations to align with communities’ own priorities and plans and to respond quickly to emergencies and changing situations on the ground,” the authors wrote.

To encourage further transparency about where funding is going, the GATC created the Shandia platform to support Indigenous- and community-led funds, to advocate for increasing direct, effective and sustainable funding, and to ensure accurate tracking of funds.

“The need for a vehicle that can help us to interact with funders continues to be a critical issue for our goal of territorial direct investment,” said Sucre Romero. “This is why we have proposed the Shandia platform and created several financing mechanisms at the national and regional level–to facilitate direct funding to our territories and communities for actions that combat climate change, conserve biodiversity and sustain our rights. Without it, we will not have the opportunity to be in the driver’s seat in designing climate solutions that work; we will not be able to influence what these donors fund and where.”

The Rainforest Pharmacy: Amazonian peoples’ resilience in the face of the pandemic

/in News/by GATCThis is a story of the peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon, an account of the arrival of COVID-19 deep in the rainforest, and how communities came together and shared their knowledge to confront the pandemic and its far-reaching impacts.

Despite the unforeseen onset of the pandemic in 2020 and the devastation it caused worldwide, indigenous peoples embraced their ancestral knowledge and faced it with wisdom and in solidarity. From the initial months of the global emergency, communities throughout the Amazon resorted to ancestral knowledge through words, chants, and the experience of their elders.

The rainforest is a market, the rainforest is a pharmacy, the largest and best we have. Like the doctors who have medicine, we also have our rainforest where we have medicinal healing plants.

Nancy Guiquita

Wisdom keeper of the Waorani People

The Route of Ancestral Wisdom

Nemo Guiquita directs the Women and Health areas of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon, CONFENIAE, where one of the projects carried out during the pandemic was the Health Route, a program designed to provide primary care to Amazonian communities, while also using ancestral wisdom to mitigate the coronavirus disease.

From the communities, we worked with wisdom keepers, youth and women to fight the disease. We had to turn once again to our community elders and start identifying medicinal plants, leaves, roots and stems. Our knowledge came back to life and has been a great achievement and strength for us.

Nemo Guiquita

Leader of the Waorani people

Nemo tells how at the beginning of the pandemic the roads were closed and the Ecuadorian State turned its back on them, but this abandonment resulted in an acceleration of the transmission of ancestral knowledge from the elders to the younger population. Families and entire communities went deep into the dense jungle to collect and then prepare the medicines that they used to treat the symptoms and alleviate the pain of the infected people.

In another part of the vast Amazon rainforest, Unión Base also experienced this rebirth of ancestral knowledge. Indira Vargas, community leader of the Kichwa people, actively participated in several training processes on COVID-19 organized by CONFENIAE, and she trained as a health Promoter.

Together with a group of women from her community, Indira is part of the Awana Collective, a space for sharing ancestral practices, experiences, and care, ranging from traditional food practices, the handling of native plants and seeds, to bonfire discussions, ancestral medicines and the role of women in community development.

For as long as I can remember, I have grown up with my grandparents in the community, and in fact, my grandparents taught me a lot about the stories and about knowledge itself. As an indigenous person, my grandmother taught me how to cultivate the land, and how knowledge is connected to the chants, says Indira about her training in the use of the vast variety of Amazonian plants.

One of the things about being a Promoter was getting to know other realities, other processes led by different nationalities. We realized that the medicinal plants were the same across all nationalities, in all the communities I had the opportunity to visit in the region.

Indira Vargas

Community leader of the Kichwa people

Indira talks about how the use of ancestral plants and medicines is consistent across the Amazonian communities of Ecuador, despite being from different territories, languages and peoples. This demonstrates a deep and intrinsic ancestral wisdom. Her work as a health Promoter is precisely a combination of ancestral and Western knowledge.

Both Western medicine and traditional medicine are good. Connecting the two would be a great step forward. It would be an intercultural construction: true interculturality in knowledge, Indira reflects.

This note is a preview of the series Resilience Stories, a TINTA (The Invisible Thread) project for the documentation and visibility of cases that show the adaptability, strength, and unity of people and communities in the face of COVID-19 in the territories that make up the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

Crafting a Visual Ecosystem: Unveiling Our New Brand

/in News/by GATCIn a world where the interconnectedness of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities is more vital than ever, the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC) has embarked on a transformative journey to redefine its identity. Over the course of a year-long process, our organisation has carefully crafted a new brand that encapsulates the spirit of unity, resilience, and unwavering dedication to the defence of our rights and territories.

Unity in Multiplicity: The Essence of Our Brand

The process of crafting a visual identity that could encapsulate the richness of cultures present within the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities was a formidable challenge. Our aim was to create a logo and visual ecosystem that not only celebrated the diversity of our members but also symbolised the united front we present in safeguarding our shared Earth. Our member organisations come from all of the richest rainforests and all have a rich cultural heritage, but in the face of difference we come together with a shared mission.

The journey began with an extensive research phase, during which we immersed ourselves in the histories, stories, and aspirations of the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities that constitute our alliance. Through dialogue with our leadership, we sought inspiration and meaning that would resonate deeply with our collective ethos. Each iteration of the design was a step towards capturing the intricate tapestry of our unity.

The meaning behind the logo

- The Circle: A symbol of life’s cyclical nature, the circle embodies our profound respect for Earth’s rhythms. We honour both times of abundance and rest, nurturing the planet as it nurtures us.

- The Rising Sun: The half sun represents dawn and hope. In an era marked by the climate crisis, maintaining hope for a brighter future is pivotal to our collective mission.

- Seeds: These seeds encapsulate our legacy. Our work is driven by the desire to leave a fertile planet for generations yet to come, ensuring our contributions resonate through time.

- Roots, Branches, and Corals: The intricate elements below represent our territories in their variety. They represent the roots and branches of vast forests, and also the deep sea corals of our coastal communities. For us roots represent our deep connection to our territories. We are committed to working with the grassroots organisations to ensure we are a legitimate actor to raise the voice of indigenous peoples and local communities. The roots also speak to us about our ancestral connections, we hear the voices from our ancestors and proudly carry our cultural heritage.

- Hands: Representing our connection to Earth, these hands simultaneously embrace our roots and cradle our growing branches. They symbolize our past, our present, and the growth that lies ahead.

Our palette

- Deep Green: Symbolic of the profound depths of nature, this colour envelops us in the power of the natural world.

- Vibrant Green: Reflecting the abundant richness of nature, this shade encompasses all that sustains life.

- Deep Red: As the colour of blood, knowledge, and rituals, deep red signifies the collective essence of our peoples.

- Orange: Representing the soil, the source of life, orange embodies the earthy foundation that supports growth.

- Ivory: This hue reflects the purity and luminosity of water, which flows through our rivers and oceans, connecting us all.

In our new visual identity, we’ve woven the stories, hopes, and aspirations of us, the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities that are guarding the future of our Earth. It stands as a testament to our unity, our growth, and our commitment to safeguarding Mother Earth. Each element of our logo carries deep symbolism, a reflection of the diverse voices and perspectives that constitute the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities. Together, we rise, we defend, and we stand as guardians of our shared home.

We extend our sincerest appreciation to Motora, the Brazilian design studio that partnered with us in this journey, they have brought our vision to life.

Yasuni Consultation: A Call to Protect the world’s most biodiverse forest against oil exploitation

/in News/by GATCThe Yasuni National Park in Ecuador, the most biodiverse place on Earth and a sanctuary for Indigenous Peoples, faces the looming threat of oil extraction that could devastate its delicate ecosystems. On August 20th the Ecuadorian people will vote on a groundbreaking consultation process to decide whether to keep exploiting oil or protect this crucial ecosystem and its cultural significance.

In the heart of Ecuador lies the Yasuni National Park, a treasure trove of biodiversity and a sanctuary for Indigenous People. The Yasuni region has become a focal point of global environmental concern due to its potential for oil extraction, which poses a grave threat to its delicate ecosystems and the livelihoods of its indigenous inhabitants. As the looming decision regarding oil exploitation in Yasuni draws near, the Indigenous Peoples raise their voices in unison to champion the preservation of this invaluable natural wonder.

Yasuni is not just a patch of land; it is a living, breathing testament to Earth’s natural wonders. It boasts unparalleled biodiversity, home to countless plant and animal species found nowhere else on the planet. It is considered to be the most biodiverse place on Earth. This delicate balance sustains intricate webs of life and plays a vital role in maintaining the global climate. The Indigenous Peoples of Yasuni have lived in harmony with this ecosystem for generations, and their stewardship has allowed its incredible diversity to flourish.

However, the lush landscapes of Yasuni now face an imminent threat – the encroachment of oil extraction. While oil exploitation might offer short-term economic gains, the irreversible damage it could inflict on Yasuni’s ecosystems far outweighs any temporary benefits. The process of drilling, infrastructure development, and potential spills could lead to deforestation, soil and water contamination, and disruption of local wildlife habitats. Indigenous Peoples, who have lived sustainably in Yasuni for centuries, are at risk of displacement and loss of their traditional way of life.

The Yasuni region is not only home to well-established indigenous communities but also harbours the rare presence of uncontacted Indigenous Peoples, the Tagaeri and Taromenane. They live in voluntary isolation, maintaining their traditional ways of life and remaining untouched by the modern world. The encroachment of oil exploitation poses an existential threat to these vulnerable populations, as contact with outsiders could introduce diseases to which they have no immunity and disrupt the delicate balance of their existence.

In a groundbreaking move, a consultation process has been initiated to determine the future of oil exploitation in Yasuni. Indigenous Peoples, who have a deep spiritual connection to the land, are playing a pivotal role in shaping this decision. On August 20th, the people of Ecuador will express their democratic right through a consultation, making their voices heard and shaping the destiny of their homeland.

The Tagaeri, Taromenane,Dugakaeri, Waorani and Kichwa peoples are organised and are calling their nation and the international community to protect the ecuadorian Amazon by voting #SíalYasuni and by supporting their campaign through digital platforms.

The Yasuni Consultation represents a beacon of hope for the preservation of one of the world’s most remarkable ecosystems. Indigenous Peoples stand at the forefront of this battle, defending their homes, cultures, and the delicate balance of nature. As the world watches, the Yasuni consultation serves as a testament to the power of unity and the collective determination to safeguard our planet’s irreplaceable treasures. Let us stand with the indigenous communities of Yasuni and ensure that this natural wonder remains untouched by the scourge of oil exploitation.

To support Indigenous Peoples in Ecuador, follow the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon and share their message (@confeniae1) and use the hashtag #SíalYasuni.

Inclusive Dialogue at Amazon Summit: Indigenous Peoples must be at the centre of all dialogues

/in News/by GATCThe Amazon Summit (8th and 9th of August) and the Amazon Dialogues (Diálogos Amazônicos) (4th to 6th of August) have sparked vital discussions about the preservation of the world’s largest rainforest and its immense ecological significance. However, it is crucial to emphasise that these discussions cannot be complete without the active involvement of the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities who have historically been the most effective stewards of this invaluable ecosystem.

The importance of this inclusive approach was underscored by the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) and various indigenous organisations during the lead up to the Amazon Summit. The Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon came together to highlight the pressing issues surrounding the Amazon rainforest, particularly the threats posed by the Time Frame (Marco Temporal) thesis and the approaching “point of no return”.

During the Amazon Summit the leaders of eight Amazon countries, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela will seek to renew the Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACT) and its related organisation (ACTO). The goal is to achieve a comprehensive agreement for the Amazon’s future. However, it is imperative to remember that any approach to preserving the rainforest must be informed by the collective wisdom of the people who have nurtured and protected these lands for generations.

Multiple studies, including recent evidence by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP), consistently support the idea that the preservation and sustainable management of the Amazon are intrinsically tied to the rights and involvement of its native inhabitants. In fact, indigenous territories in all the Amazon have lower deforestation rates than any other land, including nationally protected areas.

However, policy makers around the region are yet to commit to demarcating more lands to Indigenous Peoples, and some governments are doing the exact opposite. In Brazil indigenous peoples have been standing up against the Time Frame thesis, a legal argument that exclusively grants land rights to peoples who were present on or in contention of a specific piece of land on October 5, 1988, the day the Federal Constitution was enacted. This assertion fails to consider instances of displacement and the encroachment of settlements by land exploiters and timber merchants.

“We are more than 180 peoples in the Brazilian Amazon, and there is no way we could speak, there is no way we can dialogue about preservation without talking about demarcation of indigenous territories” , said Auricélia Arapiun from the Coordination of the Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COAIB) during the the Amazon Dialogues plenary. “We do not want a discussion in which we are not heard. We want respect for our right to Free, Prior, Informed Consent; we want to see the effectiveness of policies that protect our territories” she added.

In a recent letter written by APIB and several other organisations of the region mentioned the following: “We demand that our own forms of territorial organisation and traditional and original occupation, which are independent and prior to State recognition, be considered” and also pointed out that “Discussing the future of the Amazon without Indigenous peoples is equivalent to violating our original rights and all the work we do for human life on the planet.”

As we move forward in our collective mission to safeguard the Amazon rainforest, it is imperative to ensure that the voices of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities remain at the forefront of the conversation. The preservation of this invaluable natural treasure hinges on our ability to include and respect those who have been its guardians for time immemorial. Without their insights, traditions, and active participation, any debate around Amazon conservation would be incomplete and inherently flawed. Let us stand united in recognizing the significance of inclusive dialogue and equitable collaboration for the future of the Amazon and our planet.

To support Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities during the Amazon Summit follow and donate to the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (@apiboficial).

all photos: @cristian-arapiun

Protecting the World’s Forests Means Protecting Indigenous Rights

/in News/by Juan Carlos JintiachIndigenous Peoples have proven to be the best protectors of our world’s natural resources. But their lands and traditional ways of life are under attack by extractive corporations that prioritise profits over sustainability, posing a threat to biodiversity and the future of all.

TENA – For more than 500 years, Indigenous Peoples in Ecuador have been fighting to protect their lands, culture, and very existence from the disastrous consequences of colonisation. From the moment the colonisers set foot on our land, they sought to exploit its natural resources for profit. Today, corporations from China, Canada, and Australia mine our territories for gold, disregard our objections, and defy government orders, perpetuating death and destruction.

Indigenous Peoples have long served as guardians of humanity’s collective future, living in harmony with nature and respecting its cycles and complexities. We recognize that our survival (and the survival of all others) is inextricably linked to the health and vitality of natural ecosystems. But the forests we call home, which have sustained our communities for generations, are under attack. Once pristine rivers are now polluted with toxic chemicals, poisoning our food, land and communities.

As the relentless extraction of oil and minerals degrades our lands and rivers, the delicate ecosystems that serve as habitats for countless species are being pushed to the brink of collapse. But it is not just the physical destruction that we lament. The violation of our sacred lands is an affront to Indigenous Peoples’ spirit and resilience. Our profound bond with the Earth is the bedrock of our cultural identity. When multinational corporations indiscriminately ravage our forests, they trample on our ancestral legacy and disregard the wisdom and knowledge that have been passed down through the generations. Moreover, this devastation serves as a stark reminder that despite centuries of commodification, contemporary societies still cling to economic models that prioritise profits over the well-being of people and the environment.

As I write this, my friends, family, and I are actively challenging these companies’ harmful practices. We call them out on social media and take them to court. But our objections are often brushed aside, as Indigenous Peoples have been for centuries. This fuels a vicious cycle of poverty, inequality, and cultural disintegration.

Regrettably, my fight to protect the ancestral lands where my friends and family reside is merely a microcosm of the broader struggle to preserve our planet. An economic model predicated on maximising short-term profits, with little regard for the environmental consequences, has pushed the planet to the brink of climate catastrophe and resulted in polluted rivers, decimated ecosystems, and the displacement of indigenous communities.

Ecuador, like much of Latin America, is a victim of this economic model. Despite having freed themselves from colonialism, Latin American countries still rely on exporting commodities and amassing high-interest foreign loans to boost economic development. Ecuador, for example, exports oil extracted from the Amazon to service its debts.

As long as extractive capitalism prevails, Ecuador’s indigenous communities have no choice but to oppose it. We have tried to voice our concerns through peaceful protests, petitions, and lawsuits, and yet our pleas continue to fall on deaf ears. Given this blatant disregard for Indigenous Peoples’ basic human rights, the international community must intervene and enforce the court orders protecting our lands.

Indigenous Peoples’ ongoing struggle to conserve their lands and traditional ways of life underscores the urgent need for a radical shift in consciousness and practice. We must move beyond the narrow confines of profit-driven economies and embrace a new ethos that emphasises the well-being of individuals, societies, and the planet.

To this end, Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley’s Bridgetown Initiative calls for far-reaching reforms to the global financial architecture. Making multilateral lenders more responsive to the climate needs of low-income countries would enable critical funds to be directed to the countries that need them most, such as Ecuador. While it may be too optimistic to believe that such reforms would end gold mining in the Amazon, these changes are essential to dismantle today’s exploitative system and put the world on the path to sustainability.

In this time of crisis, let us draw inspiration from the indomitable spirit and unwavering commitment of indigenous communities that have been fighting to protect their lands for centuries. By coming together and embracing alternative economic models, we can compel multinationals to abandon their destructive practices and reclaim a future where Indigenous Peoples’ rights are upheld, our forests are safe, and the well-being of all living things takes precedence over the corporate bottom line.

Indigenous Peoples are facing multiple legal threats that could worsen the climate crisis

/in News/by GATCAfter years of fiercely defending their rights and territories against Bolsonaro’s right-wing government, indigenous peoples in Brazil and the international community were hopeful for a change with the victory from Lula, who ran for presidency with promises to protect the environment and rebuild relationships with indigenous peoples. The creation of the Indigenous Peoples Minister -led by Sonia Guajajara– and the demarcation of six new indigenous territories (some that had been waiting for 30 years to get this status) indicated the turn of an era.

However, it was short-lived; the anti-indigenous and pro-ruralist agenda still deeply permeates Brazilian politics and society. Large portions of the country are against policies that benefit indigenous peoples, granting them rights over their ancestral lands, and many claim the best way to ‘develop’ the country is through extensive soy planting, cattle ranching and so on. Despite solid evidence that these actions could worsen the climate crisis. Right now, indigenous peoples (IPs) are standing up against at least five laws and legal documents that put their lives and territories at risk. The Marco Temporal thesis ‘Time Frame’ and the PL2940/PL2903 bills want to stop indigenous land demarcation, which could give the green light to ruralist groups to invade and violate the rights of the indigenous peoples who guard biodiversity.

photo: @junomundo

Moreover, the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate and the Justice system hold members who claim there is already too much land in the hands of indigenous peoples whilst pushing for more significant concessions to mega agricultural projects, oil exploration and mining. Just last week, on the 30th of May, Brazilian deputies approved the PL2940 bill (now called the PL2903), which proposes the release of highway construction, hydroelectric plants, and other works on indigenous lands without free, prior, and informed consultation with IPs; grants authorisation to challenge land demarcation at any stage; loosens the political framework of no-contact with isolated peoples. The bill is set to be reviewed by the Senate in the coming days. The Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) has called for continuous national mobilisations to stop it and is providing live coverage of the situation.

Threats to indigenous peoples are also carried through the Justice System. The Marco Temporal thesis could turn into a harmful legal precedent soon. The text argues that indigenous peoples are only entitled to the demarcation of their traditional lands if they were occupying these lands on the 5th of October, 1988, the date of the publication of the Federal Constitution of Brazil. According to this thesis, lands occupied by other people on that date cannot be demarcated as indigenous lands. These territories can be considered the property of private individuals or the State, no longer of the original peoples who inhabit them. The thesis has been defended by rural sectors and politicians who argue that the lack of a defined date for the occupation of land occupation by indigenous people generates legal insecurity and land conflicts. However, it is widely criticised by jurists, indigenous organisations, social movements and environmentalists, who point out that the thesis is a threat to the rights of indigenous peoples and an affront to their dignity and survival. In addition, many indigenous communities were expelled from their lands during the military dictatorship and were only able to return after the date established by the thesis, which can result in serious human rights violations.

The Marco Temporal thesis could be approved on the 7th of June when the Federal Supreme Court will make a ruling on the Xokleng case -a dispute raised by the Environmental Institute of Santa Catarina (IMA by its Portuguese name) against the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples and the Xokleng people that aims to strip them from ancestral lands. If the IMA wins using the Marco Temporal legal argument, many more legal cases could follow to challenge the demarcation of indigenous lands across the country.

Scientists across the globe have shown again and again that granting indigenous peoples access to their lands is the most effective way to protect the critical ecosystems that the whole of humanity needs to halt climate change. For example, the most recent study by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project shows that indigenous territories are even more efficient at stopping deforestation and forest loss than nationally protected areas. The data is significant for Brazil, which holds the planet’s most extraordinary biodiversity and fauna; 10% of our world’s species call it home. Additionally, 305 indigenous ethnic groups inhabit these nature-filled territories, providing richness in culture and showing a way to live in connection with nature.

We are currently at a crossroads to stop the projects mentioned above that threaten the lives of indigenous peoples and, in turn, put the biomes under their guardianship at risk of destruction. The loss of nature and cultural richness in Brazil greatly harms planetary health and sets the global goals to halt climate change in jeopardy.

How can you help?

- Follow the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (@apiboficial) to be updated and share their content with the relevant hashtags #MarcoTemporalNão! #VidasIndígenasImportam #NossoDireitoÉOriginário #EmergenciaIndígena #DemarcaçãoJá!

- Follow the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (@globalalliancet & @guardiansoftomorrow_)

- Mobilise authorities, celebrities and influencers to speak up in support of indigenous peoples and our planet.

- Organise protests in front of Brazil’s Embassies, Universities, the European Parliament, etc.

- Donate here to support the indigenous mobilisation.

- Support and promote the visibility of our participation in Bonn, Germany, during UNFCCC events (LCIPP /FWG 9; Indigenous Caucus; SBSTA)